Who were the African Americans who made Mount Moriah their home? We can learn a lot about them from census records, deeds, newspaper accounts, and family histories.

Work and school: Although most men in Mount Moriah listed their occupations as “laborer,” while many women were “keeping house,” there was a variety of work available. Joseph Case was a carpenter (1850), William Peaker worked in a paper mill (1880), Charles Fields and William Case were boatmen on the canal (1870), and through the years, four barbers were listed: John H. Hall (1860), Robert J.M. Long (1870), Robert E. Kohl (1870, 1880) and Theodore M. Rodgers (1880). Elizabeth Amos was keeping house, but as a widow in her later years, she took in laundry (1870). Both black and white children in the area attended New Hope Elementary School, opened in 1851.

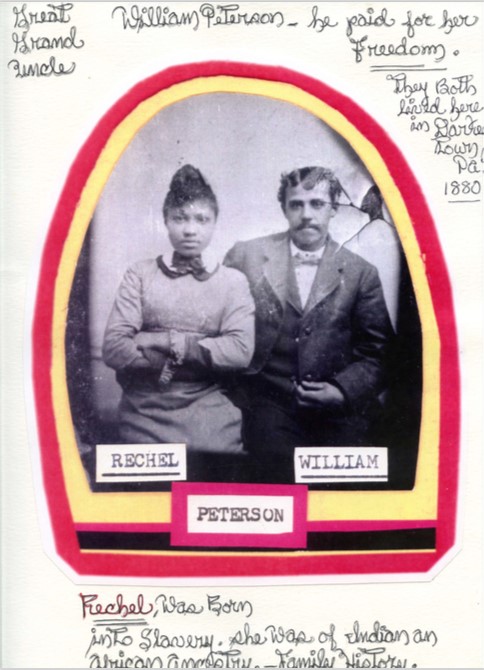

Families: Census records show that some families remained in Mount Moriah for decades. The Case, Anderson, Peterson, Hall, Moore, Peaker, Murphy, Smith, Henderson and Frost families had a lasting, multigenerational influence and helped build the church and cemetery.

Some residents were born free, while others had escaped slavery. Rachel Moore was born into slavery in Maryland. When she was manumitted (legally freed by her enslaver), her children were not, so she made the brave decision to risk being captured and escaped with all six children and traveled the Underground Railroad to freedom. According to those who aided her, the family arrived one rainy night in Pennsylvania with legs bleeding from the arduous journey (Magill, EH. When Men Were Sold, 1898). They settled in New Hope shortly before 1850 and lived at Mount Moriah for over 50 years.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Mount Moriah community members answered the call. Joseph Peaker, a church trustee, served as a corporal in Company A of the 24th U.S. Colored Infantry. Known as “Joe,” he was also a boxer who “bore the distinction of never losing a battle” (Obituary, The Beacon. May 5, 1904). Charles Fields served in the same company and was buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery, as was John Peterson, who served in Company K of the 45th U.S. Colored Troops (Solebury Historical Society, Mount Moriah Church; N.J. Civil War Records).

Homes: At Mount Moriah, African American homeownership flourished. According to census data, 93% of local residents lived outside of homes of whites in 1870, and 43% owned their own homes. Families were building wealth and financial security while attaining the higher status associated with land ownership. Deed records show that some residents subdivided their lots and sold land to family members and fellow parishioners at Mount Moriah Church.

The lasting strength of community: Over the decades, the church congregation in Mount Moriah declined. The last camp meeting was held in 1921. Eventually, the church sat empty. When it was demolished in 1959, three books were found buried with the 1869 cornerstone: The Doctrine and Discipline of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, The Hymn Book of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and The Bible. Although the residents of the Mount Moriah neighborhood moved on, the community they built helped sustain them in their focus on faith, family and providing a better future for the next generations.

If you enjoyed this three-part excerpt for Black History Month, be sure to check out the story of Mount Moriah on our Untold Stories website, launching in March. The project is made possible through a generous grant from the Alliance for Watershed Education of the Delaware River.