The American beech (Fagus grandifolia) is one of our largest and longest-lived trees in the eastern US, but the future of these grand trees is uncertain due to Beech Leaf Disease (BLD).

In 2012, northeastern Ohioans noticed that the leaves of their American beech trees were becoming banded, crinkly, and wrinkled and dying, a sure sign of distress for the tree. However, this stress was not drought or a known pest plaguing the trees. This was a new parasite: a nematode known by the species name Litylenchus crenatae subsp. mccannii (Lcm). The origins of this nematode are still unknown, but its spread can be easily tracked by the wave of beech tree mortality it leaves in its wake. In 2016, the nematode was found in northwestern Pennsylvania. By 2023, it had arrived in all of southeastern Pennsylvania. This feat of travel by creatures too small to be seen with the naked human eye would be a marvel if it weren’t for their damaging effects on some of our most impressive and valuable trees.

Beechnuts on a healthy beech tree are a valuable food source in our forests.

The American Beech Tree

Let’s take a moment to understand why American beech trees are such beloved, valuable members of our local forests. Beech is a major player in our oldest forests, responsible for providing a wealth of food and shelter within these ecosystems. They are very shade-tolerant and slow-growing trees. Beechnuts are dispersed by gravity, surface water, and the animals that seek to eat them. Some animals like bears, foxes, and turkeys eat the nuts outright, but others, like squirrels, mice, and smaller birds, cache them away, like acorns. A lucky few avoid being eaten and successfully sprout into saplings.

This method of seed dispersal is much slower than others, such as wind dispersion. As a result, beeches arrive on the scene after other tree species like maples, birches, sycamores, and tulip poplars. As such, beech saplings must be patient, waiting in the understory for the other canopy trees to fall, so that they may fill the gap left behind. A large, mature beech tree is the product of decades to centuries of good luck and steady work.

Once established, beech trees can also reproduce clonally by sending up new stems from their extensive, shallow root system. In this way, beeches create deep shade, a variety of nesting options for birds, and good cover for larger wildlife. Slower-growing trees also tend to have tougher, more decay-resistant leaves, devoting more of their energy to building up defensive chemicals. Beeches are no exception.

The long-lasting leaf litter beneath them creates additional high-quality habitat for the likes of salamanders, lightning bugs, and other invertebrates who spend part or all of their lives in the cool, damp world beneath those leaves.

Beech flowers are fairly inconspicuous, but the trees come with a bonus floral display in the form of beechdrops (Epifagus virginiana). Beechdrops are an obligate parasitic plant who live off the roots of beech trees. Beechdrops don’t produce chlorophyll or do any form of photosynthesis. Instead, they have developed root structures capable of syphoning off some of the sugars beech trees store in their own roots. The amount of sugar stolen from the beech trees is negligible, so beechdrops are not really a problem for these massive trees. Beechdrops can only do this hack to beech trees, and their ant-dispersed seeds will only germinate in the presence of these trees. Aboveground, beechdrops are small and easily overlooked, but upon closer inspection in summer, they have beautiful, tiny, purple-rimmed flowers which feed woodland bees.

The small, tan plant growing at the base of this beech tree is a beechdrop — a fascinating example of a plant that evolved to survive via parasitism rather than photosynthesizing.

About Beech Leaf Disease

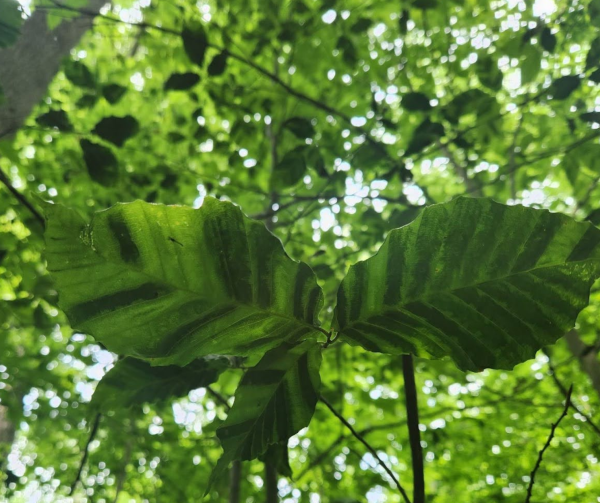

The disease caused by the Lcm nematode is known as Beech Leaf Disease (BLD), and it affects all beech species. Initial research suggests that the adult nematodes infect beech trees via their buds, but the easiest way to look for infection is in the leaves. Once the trees have leafed out, look at the leaves from below so that they are backlit by the sky. Infected leaves will have dark bands or stripes, like someone colored in between the lines of the leaf veins with a dark green marker.

As the disease progresses, you may be able to see the damage from the top of the leaves, too, in the form of yellowing and wrinkling. The nematodes may take anywhere from 2 to 10 years to kill the tree, depending on whether it is a susceptible sapling or a hardy mature tree. The infected trees are essentially being starved by the nematode, whose damage hinders the tree’s ability to photosynthesize.

Infected beech leaves will have dark bands or stripes between the lines of the leaf veins.

Possible vectors for the nematode are abundant based on initial research findings by Penn State and the USDA Forest Service. Rain, wind, caterpillars, aphids, spiders, birds, and people may all play a part in moving these tiny, tiny worms from tree to tree. Stopping the spread is likely not feasible; however, we should take care not to transport infected plant material ourselves so as not exacerbate the situation. Our solutions must be focused on resistance and recovery.

While expensive, individual beech trees might be saved by applying one of the experimental treatments of nematicides and/or a phosphite fertilizer being trialed by regional universities and tree service companies. Research on the chemical control of these Lcm nematodes is ongoing, so long-term efficacy is not yet known.

If you have a massive beech tree that has only recently become infected, consider saving it and consult with an arborist. These treatments, however, are likely not feasible on a large scale. To figure out how to help our forests weather this change and how to prevent total eradication of this tree species, we can look to the past for advice.

Lessons from Past Tree Diseases

This is not the first time a newly introduced species or disease has caused the widespread loss of a tree species in North America. American chestnut (Castanea dentata) in the early 1900s, American elm (Ulmus americana) in the 1960s-70s, and ash trees (Fraxinus sp.) today have all been hit hard by introduced pests and disease. For the chestnut, it was the Cryphonectria parasitica fungus, for the elms it was several fungi in the Ophiostoma genus, and for ash trees it’s the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) insect. The loss of these trees is a tragedy, but the silver lining is the opportunity to learn from past management mistakes and successes.

1. Look for genetic resistance by giving the trees a chance to fight back

When the American chestnut blight was on the move in the early 1900s, forest owners attempted to contain the spread by cutting down large swaths of chestnut trees while also profiting from the very valuable uninfected wood. Tragically, this effort did not work and may have killed individual trees with some amount of genetic resistance. Trees with heritable resistance traits are wildly valuable to our efforts to bring that species back from the brink of extinction. Today, trees with resistance traits are being cultivated by the American Chestnut Foundation in the hopes of one day restoring the chestnut. You can see some of these chestnut trees at Heritage Conservancy’s Fuller-Pursell Nature Preserve.

In the case of American beech management, avoid needlessly pruning and cutting down the diseased trees. Initial research has not found pruning to be an effective control, and in some cases, it may harm the tree. Only cut down severely infected trees that pose a direct hazard to people and structures. If you can let the infected trees duke it out with the nematodes, careful observation may reveal individual trees that are better than average at fighting back. Collecting seeds from those trees and attempting to propagate them may be helpful in the long term recovery of the species.

2. Species diversity is key to resilience

For the forest as a whole, more species present means less impact if one gets taken out by a new disease or pest. At one point in America’s history, the American elm was the most popular street tree. So when Dutch elm disease ran rampant, large stretches of America’s streets were left bare. Likewise, the patches of Pennsylvania forests with the highest abundance of ash trees are the places today where forest health and regeneration are most compromised in the wake of the emerald ash borer, as invasive plants move into the newly disturbed space left behind.

As a function of their survival strategy, American beech has a tendency to slowly take over big patches of forest. This tendency is not a problem in and of itself, as beech-dominated forests offer unique and valuable habitat, but it does create a vulnerability in the local ecosystem. If there are large areas with few to no tree saplings of other species, then there is less chance of those other species filling in for the dying beeches and more chance of takeover by fast-growing invasive species. Protecting existing tree saplings from deer and other herbivores, and planting additional saplings in areas with low natural regeneration, will be key to mitigating the long-term impact of beech loss in our local forests.

3. Well-funded, independent research institutions are critical to finding solutions to novel problems

As today’s researchers race to find us solutions to Beech Leach Disease, they are benefiting from the work done on previously introduced tree pests. For example, one of the experimental treatments for BLD is a chemical called Thiabendazole, which was originally developed for treating Dutch Elm Disease.

The work done by the American Chestnut Foundation to breed blight-resistant American chestnuts has served as a model for other tree resistance-breeding programs and can do so for beeches now, too. Since BLD is not the first novel disease to be caused by an introduced pest, we have the research infrastructure (i.e., research departments, partnerships, inter-agency relationships, study models, etc.) to quickly start studying the problem.

Likewise, the lessons learned from BLD contribute to our larger understanding of the natural world and may lead to other important discoveries in the future. Without this science, we wouldn’t even know what we were up against. Evidence-based, cost-effective solutions require high-quality research done by independent experts and qualified professionals.

American holly (evergreen leaves) and American beech (pale brown leaves still holding on in winter, a phenomenon known as “marcescence.”)

How to Mitigate Beech Leaf Disease

Equipped with the wisdom of the past and the new information provided from current research, we have several options for responding to Beech Leaf Disease.

1. Monitor for resistant individual trees and for disease spread to other species. These two pieces of information are crucial for our collective long-term response to BLD. If you notice specific beech trees that appear to be doing better than others of a similar size, take note of that tree and its growing conditions. You can try either propagating that tree yourself or getting in contact with researchers who may be interested in collecting its seeds. If you notice similar disease symptoms appearing in trees that are not beeches, be sure to report that to the US Forest Service’s Tree Health Survey. Currently, the members of the beech genus (Fagus spp.) are the only species known to host this nematode.

2. Replant with a diversity of native species and/or help existing tree saplings survive by protecting them from herbivores. You can protect both naturally occurring and newly planted saplings with plastic tree tubes from brands like Tubex and Plantra, or make homemade cages using metal fencing (with a minimum 5ft height) and crooked hooks. Some good species for replanting include:

Hickories, such as shagbark (Carya ovata), pignut (C. glabra), mockernut (C. tomentosa), and bitternut (C. cordiformis)

Oaks, such as red (Quercus rubra), black (Q. velutina), white (Q. alba), chestnut (Q. montana), pin (Q. palustris) and swamp white (Q. bicolor)

American Holly (Ilex opaca)

White Pine (Pinus strobus)

Black Gum aka Tulepo (Nyssa sylvatica)

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Paw-Paw (Asimina triloba)

American Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana)

Musclewood, aka Ironwood, aka Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana)

American Hazelnut (Corylus americana)

Witch Hazel (Hamamelis virginiana)

3. Remove invasive plant species, like multiflora rose, to give native plants a chance to establish themselves in the canopy gaps left behind by dead and dying beeches. It is best to start this work sooner rather than later, because invasive plants are always easier to remove when they are smaller and less established. Infected beech trees let more and more light into the understory as they lose more and more of their leaves with disease progression. As a result, invasive plant species may show up before the beech trees are even dead. At the first sign of infection, assess any invasive species present and set a game plan for removing them or at least keeping them at bay. PA DCNR has extensive information on invasive plant removal.

4. Treat the biggest, oldest trees if you have the means to hire qualified professionals. Large, old trees typically feed the most wildlife, have the most mycorrhizal connections, and take the longest to recover if lost. Treatments with chemicals such as Flouropyram (fungicide/nemicide), Thiabendazole (fungicide/nemicide), and phosphite products (fertilizer) are still experimental, and their long-term efficacy for BLD is still unknown. These products also have known impacts on species other than the Lcm nematode, so we should use them sparingly. It may be worthwhile to try to save old trees given their wildlife value, but doing so will require more product, and efficacy may depend on both the severity of BLD and the tree’s proximity to other infected trees. Keep in mind that treating beech trees for BLD will not protect them from other diseases, such as Beech Bark Disease, or from succumbing to other stressors.

5. Cut only hazard trees. In the forest, dead beech trees are great snag trees, providing shelter for wildlife even in death. Removing infected trees or leaf litter will not necessarily prevent the spread of this disease.

Replant with a diversity of native trees: white pine, white oak, shagbark hickory, witch hazel, black gum.

These options take time and resources, but we must invest in the future of our forests. In our state, literally named after its forests, our woodlands are both our heritage and our gift to future generations. We owe it to the forest caretakers of the past and the forest lovers of the future to help our woods survive the novel challenges we’ve unintentionally given them.

Additional Resources

Check out Penn State Extension, Rutgers University, and US Forest Service for more information about Beech Leaf Disease and how to manage it.

This article was written, researched, and photographed by Heritage Conservancy’s Easement Stewardship Manager, Katie Toner.