Pollinator meadows are great, but what other horticultural options are available for saving the bees?

THE PROMPTING QUESTION

Earlier this spring, the owner of some forestland with an emerald ash borer problem asked me, “I really care about saving the bees, so how can I manage my forest for bees and other pollinators?” That question was new to me. Pollinator meadows are my go-to recommendation for providing habitat for bees, butterflies, and the like, but given that Pennsylvania was once almost entirely forested, our native pollinators must know how to survive and thrive in the woods as well. My gut answer to this landowner’s question was “cultivate native flowering shrubs and trees,” but that is such a broad recommendation.

Surely there is more to say on the subject. After some deep diving into Xerces Society, PennState Extension, and other states’ extension offices’ resources, I found out that our forests have a lot to offer bees. Bees make use of a variety of forest products, from the leaf litter, spring ephemerals, and other herbaceous flowering plants in the understory below, to the towering, flowering trees and shrubs above (even the dead ones). As a starter kit to understanding bee forest ecology, here are 9 fun facts about bees, and 9 trees for bees in your backyard.

FUN FACT 1: SO MANY SPECIES!

As of 2020, there are 437 verified species of bees in Pennsylvania, and all but 23 are native to the area. One of those non-native species is the European honeybee. As their name suggests, honeybees are the ones responsible for the honey you see in bear-shaped bottles ready for your tea, apple slices, or whatever you like.

FUN FACT 2: HIVES?

Almost all PA native bees are solitary. Honeybees are the only truly social bees in PA, while 14 native bumble bee species are social through the warmer months, but spend the winter on their own. So the classic image of a bee hive is actually the exception to most bee life cycles in this part of the world, not the norm.

Side note: remember we’re talking about bees here, not wasps! Yellow jackets and their papery hives don’t count.

FUN FACT 3: OH NO, NEONICOTINOIDS!

Concern about the effects of pesticides, especially ones containing neonicotinoids, on honeybees increased after 2006 when colony collapse disorder was first observed by honeybee beekeepers on a large scale. While only honeybees are at risk of colony collapse, bumble bees are actually 2-3 times more sensitive to neonicotinoid pesticides than honeybees.

FUN FACT 4: NO MOW MAY.

Clovers, common violets, and dandelions are all common “weeds” found in lawns that bees appreciate much more than we do. These early bloomers provide food for bees emerging from hibernation in early spring when few other plants are blooming. You can contribute to bee conservation just by waiting until later in the spring to mow, not using weed killers and lawn fertilizers, and learning to enjoy these flowering species in your lawn.

FUN FACT 5: HOME IS WHERE…

About 70-90% of native bee species are ground-nesters, with the rest generally living in wood and hollow stems. Leaf litter, dead wood, loose earth, and abandoned rodent burrows, even pinecones and snail shells, might look messy or worthless to us, but are all valuable habitat spaces for bees. Not raking your leaves and leaving some dead wood on your land are great ways to support your local bees (and lightening bugs!) without much extra effort on your part.

FUN FACT 6: FOREST-LOVERS

Recent studies have estimated that about ⅓ of all native bees are forest specialists, meaning that they forage and nest entirely within forests, likely never venturing into meadows. Within forest ecosystems, spring ephemerals (like trout lily and spring beauty) and blooming trees (both wind-pollinated and insect-pollinated species) are important pollen and nectar sources, especially early in the spring.

FUN FACT 7: PICKY EATERS

About 15% of bees are pollen specialists, meaning that they collect pollen from one or a few species of plants. One specialist species is the squash bee (Eucera pruinosa), which seeks out the pollen of squash and pumpkin flowers (plants in the Cucurbit family). Willow trees support six pollen specialist bees in Pennsylvania, while dogwood trees and highbush blueberries each have three pollen specialists.

FUN FACT 8: BEE DIET

Pollen provides bees with protein, while nectar is their source of carbohydrates (aka sugar!). On the flip side, from the flowering plant’s perspective, pollen is the cargo they want transported to another flower, while nectar is an added incentive for the pollinator to visit. For the most part, bees need less pollen in their diet than is produced by the plant, thus allowing this mutualistic relationship to work.

FUN FACT 9: THE NEXT GENERATION

The female bees of most solitary native bees bear the responsibility of creating nests for their eggs and building up the pollen stores to get their offspring through the winter. Their male counterparts are generally much less active and only need a little bit of pollen to maintain their bodies.

TREES FOR BEES: IN ORDER OF FIRST BLOOM (EARLIEST BLOOMERS TO LATEST)

- Willows (Salix spp.), esp. pussy and black (S. discolor and S. nigra) – both pussy and black willows are medium-sized, water-loving trees that start blooming in March, or even as early as February in the case of pussy willows. Willow “flowers” are actually catkins, a cylindrical spike of clustered flowers that don’t have petals. The black willow’s catkins are yellow and longer than that of the silver, fluffy-looking pussy willow. As mentioned earlier, willow trees have a special relationship with 6 native bee species, but they’re visited by more than just those six. Willows are also well liked by many butterflies, both in their caterpillar and butterfly forms.

- Red maple (Acer rubrum) – a large, fast-growing and common tree, red maples have red blooms in March and April, and bright red foliage in the fall. Red maples prefer moist-to-wet soils, but can really do well in many different conditions. Technically red maples are wind pollinated, not insect pollinated; however, that doesn’t stop bees from enjoying the flowers’ pollen and nectar.

- Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) – A small tree that can also be more of a large, multi-stemmed bush, redbuds are early bloomers with their electric magenta flowers showing up as early as March and lasting through the spring. The redbud likes full sun and somewhat moist but well-drained soils. If more shaded, it can handle drier soils.

- American wild plum (Prunus americana) – closely related to cherry trees, wild plum’s white flowers look very similar to the more famous cherries but come in smaller clusters on a much smaller tree. Wild plums bloom in April and May and are visited by a wide variety of bees, whose pollination work makes the plum fruits possible. These fruits are then enjoyed by many birds. This is a good tree for drier locations.

- Basswood (Tilia americana) – American basswood is a medium-large tree with white summer blooms (June-July). Basswood is particularly well-liked by honeybees, as well as other charismatic invertebrates like lightning bugs, mourning cloak butterflies, and red-spotted purple butterflies. Basswood grows well in very medium-moisture soils and full sun if it can get it.

- Blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica) – Blackgum, also known as Sourgum, also known as Tulepo, is a tree that can get up to ~60 ft. tall with subtle green flowers emerging from late spring into early summer. To us, this tree is much more striking in the autumn as its leaves turn a bright red-orange color, but the Xerces Society notes that blackgum’s subtle green flowers get moderate visitation from about 46 different bee species, based on a study in Maryland. Blackgum does well in a wide range of soil conditions from wet to dry and even tolerates road salt exposure.

- Black cherry (Prunus serotina) – Cherry trees as a family are known for their beautiful white-pink spring flowers. Black cherry is one of the biggest cherry trees (60-80 ft), and its white flowers put on a show from late spring into early summer. The cherries that form from the pollinated flowers are also very ecologically valuable as a food source for many birds and mammals. These ecologically valuable trees are not very shade tolerant but can handle some drought and road salt.

- Silky dogwood (Cornus amomum) – A small tree, the native silky dogwood blooms in the summer, later than many other dogwoods. As mentioned before, there are three known dogwood pollen specialist bee species. The silky dogwood can handle full shade and a wide range of soil conditions. It does especially well in moist sites, and when thriving, can form a thicket.

- Winged sumac (Rhus copallinum) – Another small tree that blurs the line between shrub and tree, winged sumac produces abundant white blooms from July to September, making it the latest blooming tree on this list. By September, some native bees may have already started hibernating, while others, like bumblebees, are still busy as ever. Winged sumac is a good option for those drier sites with low-quality soil and exposure to road salt.

IN CONCLUSION

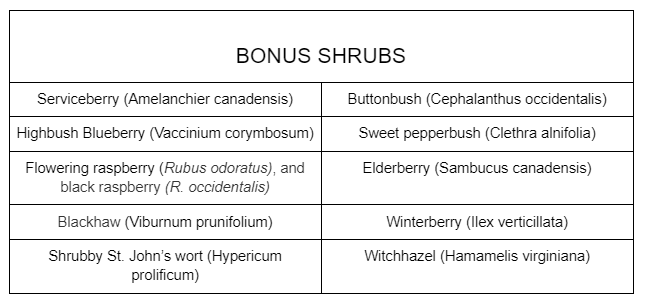

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for taking an interest in the ecology of Pennsylvania’s native bees. I hope this list provides you with inspiration for your land or perhaps just a reminder to notice and appreciate the bees buzzing around your backyard already. Below are the references I used to build this list, which is by no means exhaustive. If you are looking for more information, I would highly recommend starting with these links, especially the Xerces Society’s Delaware Native Plants for Native Bees, which is designed for Delaware but largely applies to southeastern PA as well. It provides a lot more detail about each tree’s preferred growing conditions and which types of bees are attracted to them. Lastly, I’ve included a link to PA’s Department of Conservation and Natural Resource’s list of native plant purveyors to make tracking these trees and shrubs a bit easier.

Happy gardening!

Katie Toner, Heritage Conservancy Conservation Easement Steward

FURTHER READING

Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences: Pollinator Network

PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources: Where to Buy Native Plants

Penn State Extension: Bees in Pennsylvania – Diversity, Ecology and Importance (2020)

Penn State Extension: Native Shrubs for Pollinators (2022)

Xerces Society: Delaware Native Plants for Native Bees (2019)