Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius)

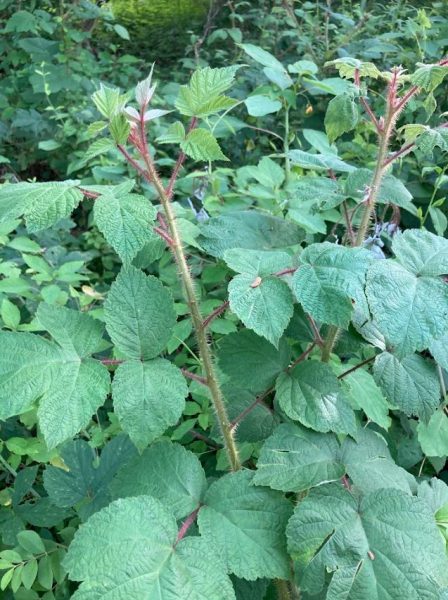

Have you ever been out on a midsummer night stroll and spotted a red fruit growing on a prickly bramble? With the fruit itself made up of a cluster of small red berries, your instinct might lead you to believe that it is a raspberry. However, upon closer inspection, you notice that the plant’s stem is covered in thick, stiff, red hairs. These are wineberries – an invasive plant that provides tasty summer treats that you can find throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Delaware Valley.

ABOUT WINEBERRIES

Wineberries are a close relative of our native raspberries and blackberries, most likely introduced to the eastern shores of the U.S. in the late 1800s as breeding stock for cultivating new varieties of berries. Like their native counterparts, wineberries are sweet and juicy; many species, including humans, deer, chipmunks, box turtles, and birds, all enjoy their savory taste.

Interestingly enough, their sweet flavor is part of their survival strategy. The seeds inside the berries are designed to survive the journey through an animal’s digestive system and germinate better afterward. By the time a bird or another animal defecates the seeds, they have likely moved far away from the parent plant and, in turn, created a brand new patch of wineberry.

Unlike their native counterparts, wineberries are more aggressive spreaders and more thoroughly exclude other plants. Wineberry thickets can get so dense and wide that they prevent tree saplings from taking root, inhibiting forest regeneration after disturbances like bad storms or pest infestations.

The delicious berries make wineberry so problematically prolific, but they also give us a tasty opportunity to take action. The more wineberries we eat, the more wineberry seeds end up in our wastewater treatment system, and the fewer end up in viable growing locations. To make life even easier for us, you can pretty much use wineberries as a 1-to-1 substitute for raspberries and blackberries in the recipes you already have. Wineberries are a wonderful treat that you can harvest yourself and use in many recipes!

HARVESTING WINEBERRIES

Harvesting wineberries is very similar to other berry pickings. Wineberries tend to be ready from late June to early July. Make sure to act fast, since many other animals like to eat them as a snack! Once you confidently identify the wineberry plant by looking for its telltale thick red thorny stem and prickly leaves, examine the health of the plant and the berries on the plant. Use caution when picking the berries; only pick those that are a nice red color and look safe to eat. Don’t pick any berries if they look like they’ve been nibbled on by another critter! Additionally, the prickly red stem is sharp and can stick to you and your clothes, so be careful of the prickers.

To harvest the berries, pull gently on the top of the berry and it will pop off of the plant. Use a container to collect your berries in. Once you collect the number of berries you’d like, wash them before eating.

Wineberries are delicious enough to eat plain. However, if you’re looking to try them in a dish, see a few ideas of ways to use wineberries below:

- Use wineberries in beverages like smoothies, raspberry lemonade, or maybe raspberry margaritas.

- Top yogurt, oatmeal, or ice cream with wineberries.

- Make a wineberry sorbet.

- Make a wineberry jam, jelly, or compote.

- Bake a wineberry pie.

- Use wineberries in the place of raspberries or other berries in virtually any recipe! They do, however, tend to be on the more bitter side, so pairing with a sweeter berry is a nice addition.

*IMPORTANT NOTES OF CAUTION*

- Only eat plants that you can confidently and accurately identify. If you aren’t sure, consult resources like plant ID apps (iNaturalist, Seek, etc.) or someone with more experience whose identification skills you trust.

- Only harvest plants growing in conditions where they likely haven’t been exposed to pollution or chemicals like road treatments, herbicides, and pesticides. While washing your foraged food helps protect you, some harmful chemicals can be absorbed into the plant’s body and can’t be washed away. One way to assess risk is to talk to whoever stewards the land in question.

- Make sure to only forage in places where you have permission to do so. This is another reason to talk with whoever stewards the land you want to forage on. Everyone should be on the same page about where you are allowed to go, and what you are allowed to take in which quantities.

Even though they’re an invasive species, wineberries are a tasty, sweet summer treat that you can find throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Delaware Valley. Going berry picking is a fun activity for people of all ages, and it is neat to pick and eat food that grows right outside your door! It is incredible to think that foraging was a primary food source for humans thousands of years ago, and something that we can still participate in today. As our ecosystems shift and change around us, foraging links us to the past while providing an opportunity to connect with our present surroundings and to participate in shaping the future. Happy foraging!

Katie Toner, Conservation Easement Steward, Heritage Conservancy

and Melissa Lee, Community Engagement Associate, Heritage Conservancy

Read more Nature Notes articles about mushrooms, native plants, and wildlife.

Learn more about Heritage Conservancy’s work to protect and steward natural lands, and get involved in our efforts.